On May 15, 2024, discussions began in the Government’s deliberative councils on the revision of the Strategic Energy Plan. The Strategic Energy Plan is the framework of Japan’s energy policy. Since more than 80% of Japan’s greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions come from energy sources, it is important to pay close attention to the contents of the Strategic Energy Plan, which sets the future composition of power sources (energy mix) and policy direction for thermal power generation, including coal-fired power.

Focuses of the revision of the Strategic Energy Plan

As issues for further discussion, the Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry (METI) has identified 1) GX and energy efficiency on the demand side; 2) decarbonization of power sources (renewable energy, nuclear power, decarbonization of thermal power through hydrogen / ammonia, CCS, etc.), grid development and storage batteries; 3) resource strategy including key minerals and decarbonized fuels; 4) power system reform and improvement of the energy business environment; and 5) the energy mix. The GX Executive Committee, established at the Prime Minister’s Office, is expected to discuss these issues, taking into account the status of discussions by the GX Executive Committee.

The major preconditions for formulating an energy policy should be, 1) a GHG reduction target consistent with the Paris 1.5°C target to prevent further climate change; 2) realizing the shift away from fossil fuels and phase-out of coal-fired power generation as has been committed to in international agreements; and 3) implementing the international agreement to triple renewable energy and double energy efficiency. However, none of these have been indicated by the Japanese Government.

Meeting the energy targets of the 6th Strategic Energy Plan is currently in jeopardy

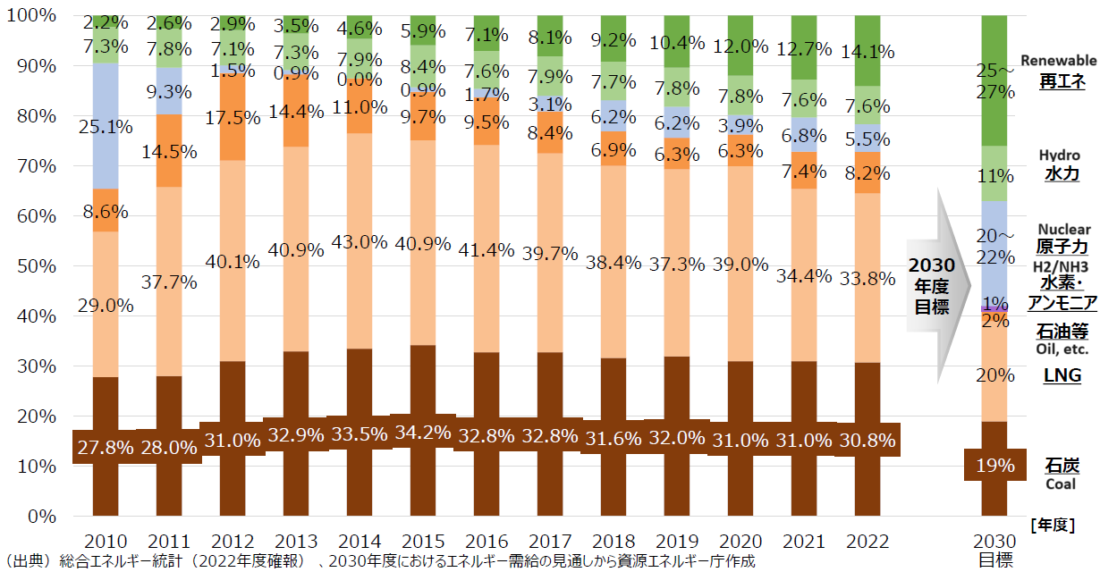

The energy mix in 2030 as indicated in the current 6th Strategic Energy Plan includes 19% coal power and 20% LNG, but under current policies, it is extremely likely that even this unacceptable ratio will be significantly exceeded.

The chart below, prepared by Japan’s Agency for Natural Resources and Energy, shows the annual amount of electricity generated from different power sources up to FY2022. It can be seen that if this trend continues, the achievement of the FY2030 target of the 6th Strategic Energy Plan will be in jeopardy.

Furthermore, according to the Aggregation of Electricity Supply Plans for FY2024, released in January 2024 by the Organization for Cross-regional Coordination of Transmission Operators (OCCTO), which compiles the outlook for electricity demand over the next 10 years from electricity operators, thermal power generation will still account for about 60% of electricity in 2033, significantly higher than the FY2030 target.

| Power source composition in 2022 from the comprehensive energy statistics (FY2022 confirmed data) | Energy mix for FY2030 as stated in the 6th Strategic Energy Plan | Predicted composition of power sources in 2033 in OCCTO’s Aggregation of Electricity Supply Plans for FY2024 | |

| Coal | 30.8% | 19% | 29.2% |

| LNG | 33.8% | 20% | 28.6% |

| Petroleum, etc. | 8.2% | 2% | 2.6% |

| Renewable Energy | 14.1% | 36~38% | 33.5% |

| Nuclear | 5.5% | 20~22% | 6.0% |

| Hydrogen/Ammonia | – | 1% | – |

Issues regarding the 7th Strategic Energy Plan

The Japanese Government is expected to link this revision to its “GX2040 Vision”, continuing the fundamental course it has been following and repositioning its policy on decarbonization strategies to include the use of hydrogen and ammonia as baseload fuels. In July last year, the Cabinet approved the Act on the Promotion of a Smooth Transition to a Decarbonized Growth-Oriented Economic Structure (“GX Promotion Act”), and in February this year, the Act on Promotion of Supply and Utilization of Low-Carbon Hydrogen and its Derivatives for Smooth Transition to a Decarbonized, Growth-Oriented Economic Structure (“Hydrogen Society Promotion Act”) and Act on Carbon Dioxide Storage Businesses (“CCS Business Act”). Japan is trying to put its own unique decarbonization policies into action, but there are a number of problems to overcome.

- Japan’s position on coal-fired power reduction measures questioned

Currently, coal-fired power generation accounts for about 30% of Japan’s electricity generation. At the recent G7 Ministers’ Meeting on Climate, Energy and Environment, the participants agreed to phase out existing unabated coal-fired power plants by 2035, but Japan is the only G7 country that has not set a target year for a coal-fired power phase-out. The problem here is the interpretation of “abated” and “unabated”. There is a widening gap between the rest of the world and the Japanese Government, which believes that if measures (including ammonia co-firing) are taken to try and limit the temperature increase from pre-industrial times to 1.5°C, then coal-fired power can continue to be used for the foreseeable future.

In light of the fact that the European Union is considering the introduction of a system of charging for imports from countries and regions without adequate environmental regulations (border carbon tax), Japan’s position toward coal phase-out measures will have a significant impact on economic activities. If the 7th Strategic Energy Plan is perceived as Japan’s reluctance to decarbonize, it will have a significant impact on the competitiveness of companies

2. Hydrogen and ammonia do not meaningfully contribute to decarbonization

Under the Green Transformation (GX) policy, the public and private sectors are promoting the use of fuel ammonia and hydrogen and the implementation of carbon capture and storage (CCS) as a measure to reduce emissions from coal- and gas-fired power generation. The goal is to increase the ammonia co-firing ratio to 50% by the early 2030s, but at this point, the technical and economic feasibility is viewed as low, and from a scientific standpoint, the reduction effect of hydrogen and ammonia is also considered to be very low.

Furthermore, even if this technology is perfected, CO2 emissions from the production and supply of hydrogen and ammonia remain a major problem. Even if the CO2 emitted during production could be captured, there are still only a limited number of suitable sites where it could be stored, and there have been very few successful examples of this worldwide. Continuing to use fuel ammonia and hydrogen under government support for CCS and fossil fuel-based thermal power generation will not contribute to decarbonization, and it will also increase the burden on consumers if the increased costs of hydrogen and ammonia production and CO2 treatment (CCS costs) are added to electricity prices.

3. The urgent need to expand renewable energy

Although the percentage of renewable energy in Japan is gradually increasing each year, it is still not enough, and output curtailment (stopping the generation of renewable energy in order to give priority to thermal power) is also increasing. Because Japan lags behind other countries in introducing renewable energy, it is necessary to significantly expand renewable energy while reducing the ratio of thermal power generation. As of now, there is no indication of how Japan will contribute to the goal of tripling the world’s renewable energy generation capacity by 2030, one of the agreed upon outcomes of COP28. Japan needs to set a clear goal in the 7th Strategic Energy Plan and work on expanding and connecting renewable energy.

4. Energy stability and security

At a press conference in March, Prime Minister Kishida stated his intention to initiate the revision of the Strategic Energy Plan and emphasized the importance of energy policy from the perspective of economic security, stating that “the current situation, in which tens of trillions of yen are hemorrhaged overseas from energy imports, must be changed” and that “the implementation of a national strategy to shift to an energy structure that will lead to decarbonization and strengthen domestic earning power is inevitable”. However, promoting measures to import huge amounts of hydrogen and ammonia will not improve energy security, especially considering its low emission reduction effects and the low economic rationality of CCS/CCUS. Moreover, it is feared that this strategy will hold back a just transition toward a decarbonized society in Japan.

Although a draft of the 6th Strategic Energy Plan was released for public comment in July 2021, no major changes were made and the draft was adopted by the Cabinet without any meaningful changes. For the formulation of the 7th Strategic Energy Plan, which will determine the nation’s energy policy looking toward 2050, there are calls from all quarters for the policymaking process to involve a variety of experts, environmental groups, and citizens, rather than again being decided solely by a limited number of related parties, policymakers, and council members. We sincerely hope that the Kishida Administration will show that it is willing to listen to the voices of the people.

Related News

【News】 OCCTO: Coal-fired power projected to account for 29% of Japan’s electricity in FY2033 (Link)

【News】Can Japan’s Hydrogen Strategy really lead to decarbonization? (Link)