In March 2025, the Organization for Cross-regional Coordination of Transmission Operators (OCCTO) released its Aggregation of Electricity Supply Plans for FY2025, a compilation of electricity supply plans submitted by 1,974 electric utilities.

These supply plans prepared by electric utilities show their planned supply of electricity and the development of power sources and transmission lines for the next 10 years (from FY2024 to FY2034).

At the 2024 G7 Leaders’ Summit, the G7 countries agreed for the first time to “phase out existing unabated* coal power generation in our energy systems during the first half of 2030s, or in a timeline consistent with keeping a limit of 1.5°C temperature rise within reach, in line with countries’ net-zero pathways”

*The term “unabated” in international agreements refers to power plants that, according to the IPCC, have not taken measures to reduce emissions by 90% or more.

Although it is necessary to set a path for reducing coal-fired power generation in a manner consistent with this agreement, this aggregation of supply plans shows that coal-fired power is expected to continue to account for a significant share of Japan’s power generation even in FY2034.

Furthermore, from this aggregation, hydrogen and ammonia are classified as “New Energies, etc.” in the same category as solar and other renewable energy sources and storage batteries. However, it is expected that most hydrogen and ammonia utilized will be produced from fossil fuels**, so lumping them together with renewable energy is misleading. Therefore, in this article, we will not lump them together as New Energies, but instead will separate them by power source.

** According to the International Energy Agency (IEA), less than 0.1% of hydrogen will be produced by water electrolysis from renewable energy and other sources in 2023. The rest will be produced by fossil fuels.

Although this report is a compilation of the 2025 supply plans submitted by registered electric utilities at the end of February 2024, it can be used as a reference to predict future trends, as past results have been close to those stated in the plans.

Coal to account for 25% of Japan’s energy mix in FY2034

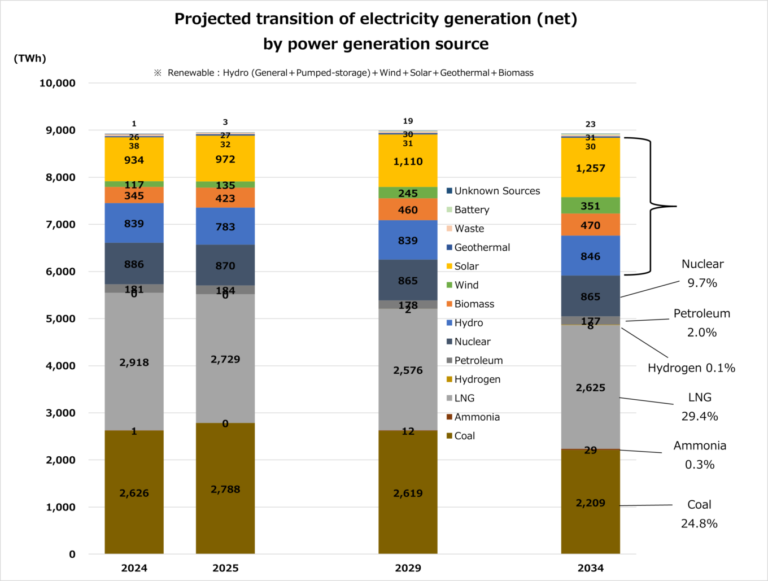

The figure shown at the beginning of this article shows the power source composition for FY2024, FY2025, FY2029, and FY2034, estimated based on the amount of transmission-end electricity supply. The power source composition does not change significantly, although renewable energy is expected to increase somewhat, and coal and LNG decrease over the 10-year period.

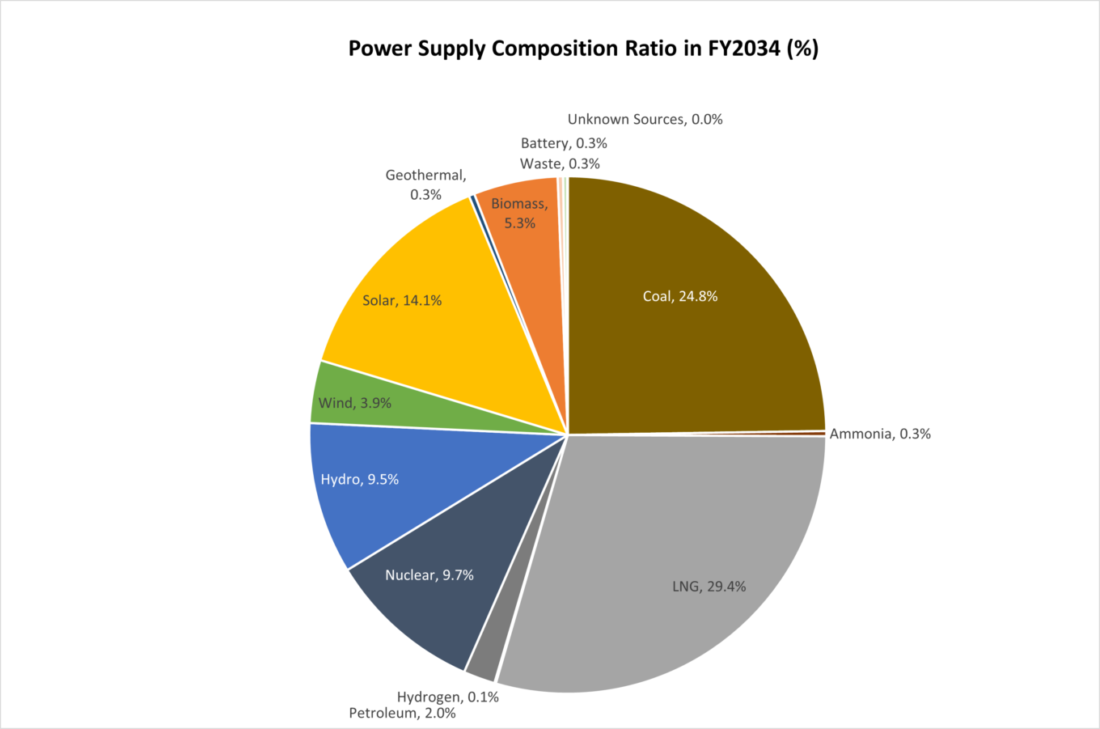

The following chart shows FY2034: coal and LNG are projected to account for about 25% and 30% of the power supply mix in the mid-2030s, respectively, with thermal power accounting for more than 56%.

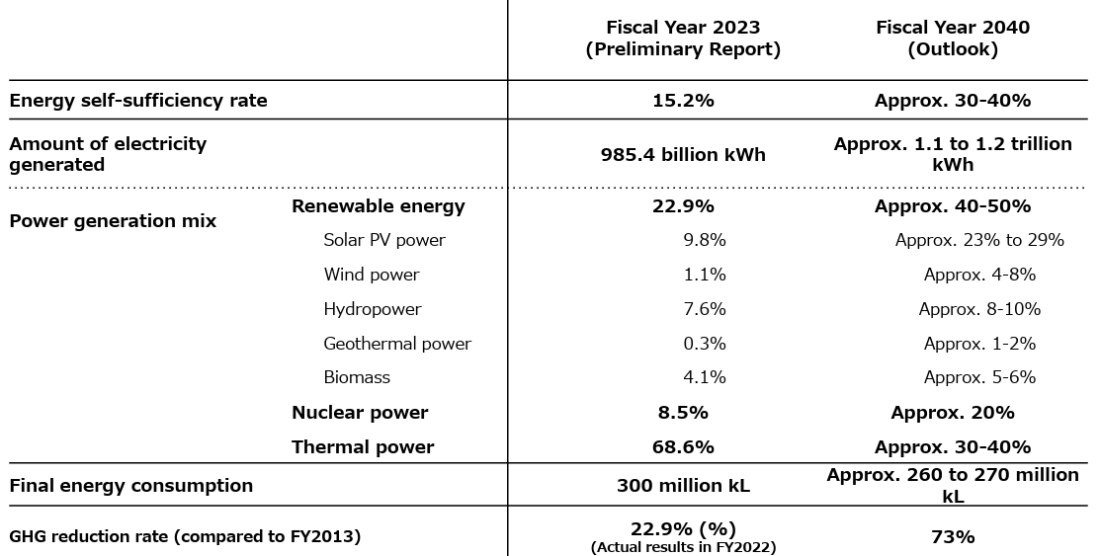

The percentage of coal- and LNG-fired power expected in FY2034 far exceeds even the FY2030 targets (coal: 19%, LNG: 20%) stated in Japan’s 6th Strategic Energy Plan. The forecast of the amount of electricity at the transmission end does not reveal any clear direction for achieving these targets.

At a time when Japan needs to set a course for reductions of coal and LNG, this high dependence on fossil fuel-based power is very problematic from an international perspective.

※The energy targets of the 6th Strategic Energy Plan are as follows:

Renewable energy: 36-38% (Geothermal, Biomass, WInd, Solar, Hydro)

Coal: 19%

LNG: 20%

Petroleum, etc.: 2%

Nuclear: 20-22%

Hydrogen/ammonia: 1%

This calculation is based on adding up the amount of electricity generated, starting with those with the lowest operating costs, and does not take into account the effects of institutional measures or the future operating status of nuclear power plants. For example, starting this fiscal year, measures are planned to be taken in the capacity market to limit the operating rate of inefficient coal-fired power plants to 50% or less, and so we will be closely watching how this will affect us in the future.

However, it should not be assumed that voluntary shutdowns will increase and Japan will “actually move closer to the energy mix targets” (p. 25) if institutional measures are taken into account. This is because the aforementioned systems have not been developed to calculate their effects or to make policy decisions to achieve the specific targets of Japan’s Strategic Energy Plan or NDC.

In addition, hydrogen and ammonia are often treated as if they are the “key to solving climate change,” but even in 2034, hydrogen and ammonia will account for only 0.1% and 0.3% of the power supply mix, respectively. For hydrogen and ammonia to make a real impact on addressing climate change, they would need to be made from 100% renewable energy sources (“green” hydrogen/ammonia) and be immediately ready for use as the main fuel for thermal power, but these technologies are still being developed and demonstrated, and there is no prospect of securing an adequate supply of green hydrogen and ammonia.

It is clear that these technologies are unlikely to make their presence felt even after this critical decade where swift climate action is required. There are serious concerns that the so-called “decarbonization of thermal power” touted by thermal power plant operators will simply extend the life of thermal power plants and end up wasting crucial funds that should instead be invested in expanding renewable energy.

No progress in reducing coal consumption, and an increase in LNG

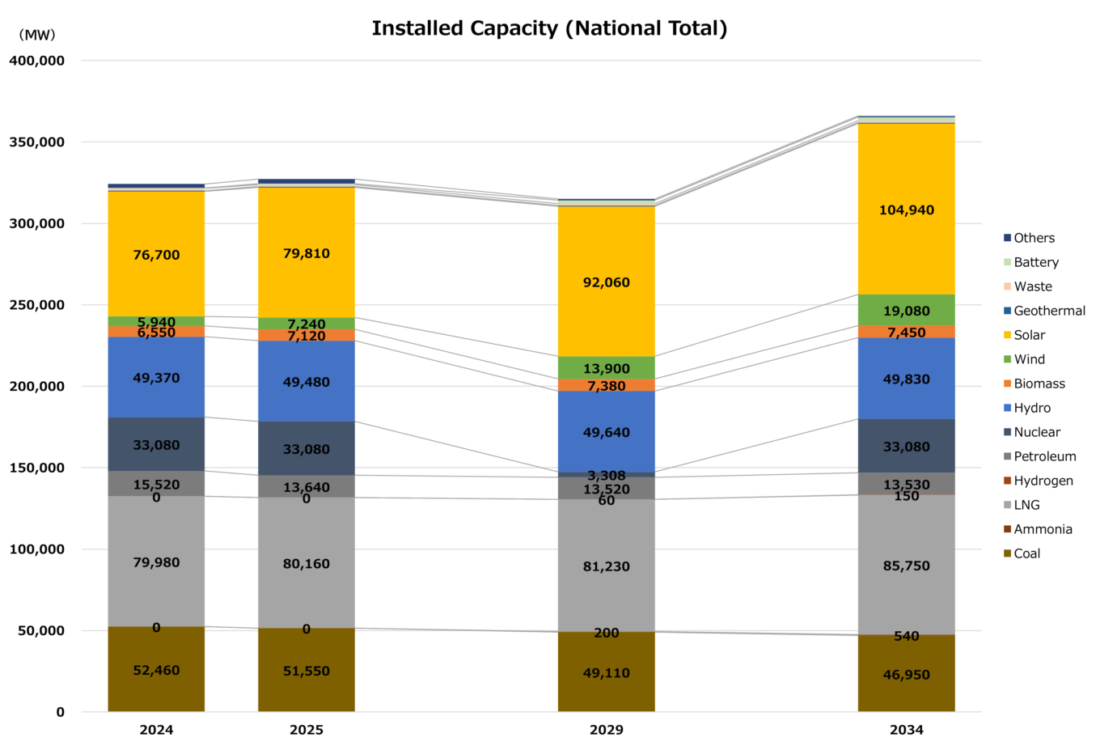

Total installed capacity (output of power generation facilities) is expected to increase over the next 10 years. The increase is particularly driven by solar power, but LNG is also projected to increase by 6 GW. A major factor in this is thought to be the fact that new LNG-fired power generation is eligible for support under the Long-Term Decarbonization Power Source Auction and other systems.

Although coal-fired power generation is decreasing, it is estimated that 47 GW (equivalent to about 47 nuclear power plants) will remain operating in 2034, indicating that Japan is far from the G7 commitment to “phase out existing unabated coal power generation in our energy systems during the first half of 2030s”.

Progress in new thermal power facilities and power plant retirement plans

As of April 2025, there are 159 coal-fired power plants in operation across Japan (excluding suspended plants). If Japan’s commitments to the Paris Agreement and G7 to limit the global temperature rise to within 1.5°C are to be honored, unabated coal-fired plants must be phased out by the early 2030s.

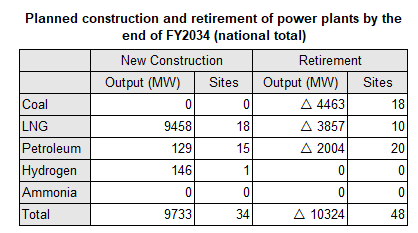

The following are the plans for new thermal power plants to be built or phased out over the next 10 years, as stated in OCCTO’s report:

Although there are no plans for new coal-fired thermal power plants, only 18 plants are planned for retirement. This is an increase of 10 sites, or 3 GW, from last year’s report, which shows a trend toward reduction of coal-fired power, but this is still only a little more than 10% of the total.

Moreover, we can see that the amount of new LNG constructed will exceed the amount of coal and LNG planned for retirement, which is completely counter to measures to address climate change.

One of the reasons for the lack of progress in retiring thermal power plants is the government’s policy of “maintaining and securing the generation capacity (kW) necessary for an overall stable supply of thermal power, while reducing the amount of power generated (kWh), mainly from inefficient coal-fired thermal power plants” (7th Strategic Energy Plan).

In other words, the policy is to reduce the amount of electricity generated without eliminating power plants in preparation for power shortages due to increased electricity demand and seasonal fluctuations. However, maintaining power plants is costly, and reducing thermal power facilities should be the foundation of an effective decarbonization strategy.

In a written opinion submitted to the Minister of Economy, Trade and Industry in conjunction with the submission of this report, OCCTO has called for institutional consideration of “measures to maintain thermal power plants that operate at even lower capacity trending toward carbon neutrality, and to utilize them as supply capacity, balancing power, and inertia function, etc.”.

However, it is questionable whether it is economically rational to spend government funds or increase the burden on consumers to constantly maintain power plants that would operate only during high demand periods such as summer and winter. Maintaining old thermal power plants not only delays the transition to renewable energy and runs counter to reducing greenhouse gas emissions, it may also increase the burden on the public. Shouldn’t the nation’s electric power system be reviewed and evaluated based on its overall benefits to society?

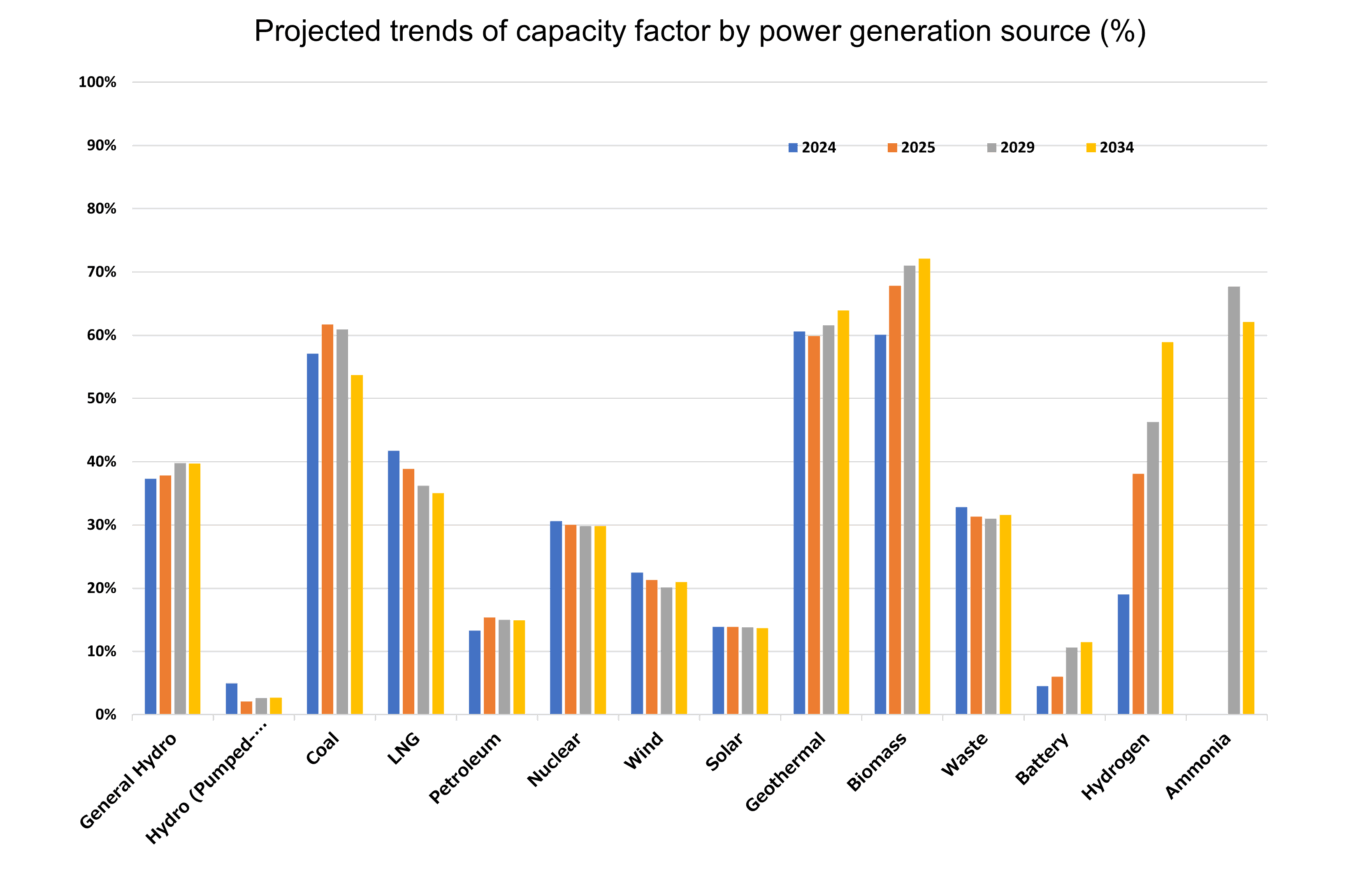

Utilization rate of coal-fired power plants stays at around 60%

The utilization rate (capacity factor) of coal-fired power plants was around 75% at the time of OCCTO’s 2016 compilation, but it has been declining in recent years and is now below 60% (from the Kiko Network report “Pathway to 2030 as seen in trends from OCCTO’s ‘Aggregation of Electricity Supply Plans’”). However, coal-fired power is expected to maintain a high operating rate, and so if the government is to “reduce the amount of electricity generated,” as it states, further action is required.

Furthermore, the capacity factor of LNG-fired power plants has also been declining, and this trend is expected to continue. When we take into account the aforementioned capacity factors, utilization rates will decrease while new construction and replacements will increase. This seems very likely to lead to excess capacity and stranded assets- with this in mind, would plant operators still want to build them?

Conclusion

Although coal-fired power generation has been on a slight decline in recent years, Japan is still not on a path toward serious reduction. There is only a short time left to reach the important milestone of phasing out coal-fired power generation in developed countries by 2030, a goal necessary to limit the global temperature rise to within 1.5°C. At the current pace, coal-fired power generation in Japan will never be phased out by 2030. Japan Beyond Coal calls for Japan to reduce coal-fired power generation and fulfill its international responsibilities, and to present a detailed reduction plan for the future within this fiscal year.

Reference

【News】 OCCTO: Coal-fired power projected to account for 29% of Japan’s electricity in FY2033 (Link)

【News】 OCCTO reports shine a light on Japan’s continued reliance on thermal power (Link)