The Japanese government and power utilities have been promoting that Japan’s coal-fired power plants are “highly efficient” from a climate change countermeasures perspective and “clean” with advanced air pollutant removal technologies.

In such circumstances, Japan has three units that use IGCC (Integrated Coal Gasification Combined Cycle), which is described as the “world’s most advanced coal technology” They are the Nakoso IGCC (525 MW) and the Hirono IGCC (543 MW) in Fukushima Prefecture, and the Osaki IGCC (166 MW) in Hiroshima Prefecture.

All three units were constructed and are being operated as demonstration plants. However, these units do not operate continuously. The prolonged downtime due to numerous problems has resulted in lower emissions of air pollutants and CO2, which ironically makes them the “most advanced clean coal-fired power plants.”

About IGCC

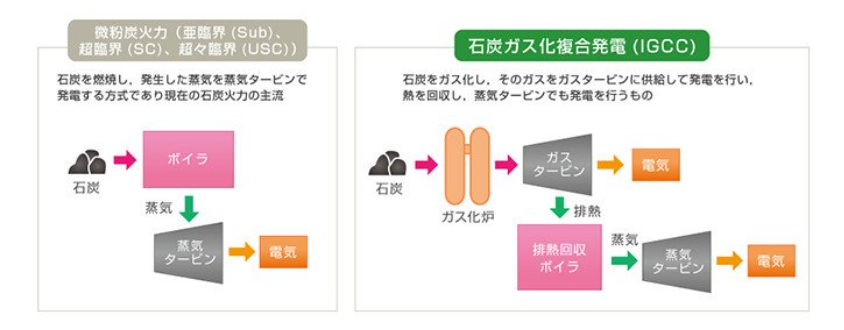

IGCC is a power generation technology that does not directly combust coal in a boiler, but instead gasifies coal in a gasifier and burns coal gas as fuel to generate electricity in both a gas turbine and a steam turbine. This results in higher efficiency and lower CO₂ emissions than regular pulverized coal-fired power generation.

There are two types of gasification: air-blown and oxygen-blown. Both of the units in Fukushima use air-blown gasification, while the development and demonstration of oxygen-blown gasification is underway at the Osaki Coolgen in Hiroshima.

Figure. Difference between regular coal-fired power generation and IGCC

Ballyhooed Fukushima IGCC Power Plant Project

In this article, JBC focuses on two IGCC coal-fired power plants built in Fukushima Prefecture, Hirono IGCC and Nakoso IGCC.

The projects of these two units began concurrently with the decision to host the Tokyo 2020 Olympics. As they were located in Fukushima, which suffered significant damage in the Great East Japan Earthquake, these units were positioned as the “Olympic Power Source*” or the “Fukushima Recovery Power Source” that would contribute to reconstruction efforts and were widely publicized.

The Hirono and Nakoso IGCC projects began with fanfare, but let’s look at what is the reality of these “clean” coal power plants.

*Since the construction delay, these units were not completed in time for the Tokyo Olympics.

Frequent Breakdowns Cause Frequent Stoppages. The Air is “Clean” Because it’s Not Operating.

Due to coal’s relatively low-cost and minimal geopolitical risks, coal-fired power plants have been considered important baseload power sources for stable supply. However, Hirono and Nakoso IGCC are not fulfilling their role at all. Data from the HJKS (power plant information dataset), operated by the Japan Electric Power Exchange, indicates that both the Hirono and Nakoso IGCC plants have been experiencing repeated long-term outages, suggesting issues with their gasifiers. Even as state-of-the-art, high-efficient coal-fired power plants, it is difficult to say whether they are operating at full potential.

Table1.Number of outages due to gasifier problems during 2021-2025

| Plant Name | Number of outages |

| Nakoso IGCC | 37 |

| HIrono IGCC | 18 |

Source: data from HJKS

The existence of inactive facilities is not good for citizens. To develop IGCC technology, substantial R&D funds have been invested through the New Energy and Industrial Technology Development Organization (NEDO). Furthermore, many thermal power plants benefit from the multiple systems, including the capacity market described below, which is designed to maintain thermal power generation. Hirono and Nakoso IGCC are no exception.

Capacity Market System Supports Power Plants Even at Low Utilization Rates

Even though Hirono and Nakoso IGCC utilization rates are very low, these units can still be supported by the “capacity market.” The capacity market is a system that pays power plants for “future generation capacity,” not for “actually generated electricity.” Its purpose is to ensure a stable power supply in the future, and compensation is paid for the power plant facility itself.

Even facilities like the Hirono and Nakoso IGCC that unstably operate with frequent downtime can still secure a certain level of revenue based on their theoretical capacity.

Table 2. Closing Bids for the Nakoso and Hirono IGCC in the Capacity Market (kW)

| 2025 | 2026 | 2027 | 2028 | |

| Nakoso IGCC Power GK | 454,750 | 454,750 | 454,750 | 454,750 |

| Hirono IGCC Power GK | 453,750 | 453,750 | 453,750 | 453,750 |

Source: from materials made by Organization for Cross-regional Coordination of Transmission Operators, JAPAN (OCCTO)

As shown in the table above, calculation based on disclosed winning bid capacities indicates that each plant may be receiving (or will receive) compensation of approximately 4 billion per year. As a result, those two Fukushima plants, which should be facing very difficult business conditions—if not stranded—given their actual power generation outputs, have instead been granted a lifeline through the system.

The fund source of the compensation paid to power utilities is incorporated into electricity bills as a “capacity contribution fee” and passed on as a burden to consumers. In this way, measures to prolong the life of fossil fuel power plants, including coal-fired plants, are being carried out almost invisibly to consumers.

The combination of decarbonization “technologies” and “systems” is the key

Government and power utility promotional materials have consistently presented “clean coal power” as if it were real, and the term has been continuously used without question.

However, looking at what is actually happening at the Hirono and Nakoso IGCC, it is obvious they have frequent breakdowns, long-term outages, low operation rates, and various problems. Even so, supported by the system, our burden continues in a way that is difficult to bring to light.

The fundamental problem with the Hirono and Nakoso IGCC is not the “technology” that doesn’t work properly. It lies in the supporting mechanisms and unquestioned policy decisions.

While power plants that are not functioning properly despite massive R&D investments are preserved by the systems, investment in renewable energy, grid infrastructure, and storage batteries—which are truly necessary for decarbonization—has been put on the back burner. Fukushima Prefecture has the largest installed capacity of coal-fired power plants in Japan. Though Fukushima is promoting community-led initiatives to expand renewable energy adoption, at the same time, coal-fired power plants riddled with numerous problems are preserved by national policies. The necessary cost has already been passed on to our daily lives in the form of higher electricity bills.

It is necessary to fundamentally reassess policies centered on and preserving thermal power, including the capacity market, and shift towards a power system centered on renewable energy.