As one of Japan’s decarbonation policies, Carbon Capture and Storage (CCS) and Carbon Capture, Utilization and Storage (CCUS) are steadily underway under the Green Transformation (GX) strategy.

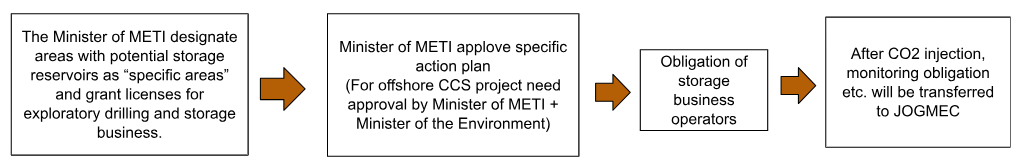

In July 2024, the Cabinet approved the “Act on Carbon Dioxide Storage Business (CCS Business Act)” for the purpose of promoting CCS projects, from separation and capture of CO2 to transportation and storage. The Act went into effect on August 5, 2024. The Japanese government has set a goal to store 6-12 million tons of CO2 annually by 2030, and 120 to 240 million tons of CO2 by 2050. On February 5, 2025, the Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry (METI) launched a “working group on considering support framework for CCS projects” to design a detailed support system for CCS projects that aim to be commercialized by FY2030, and has begun studying specific measures. It’s interim report is planned to be compiled by mid-FY2025.

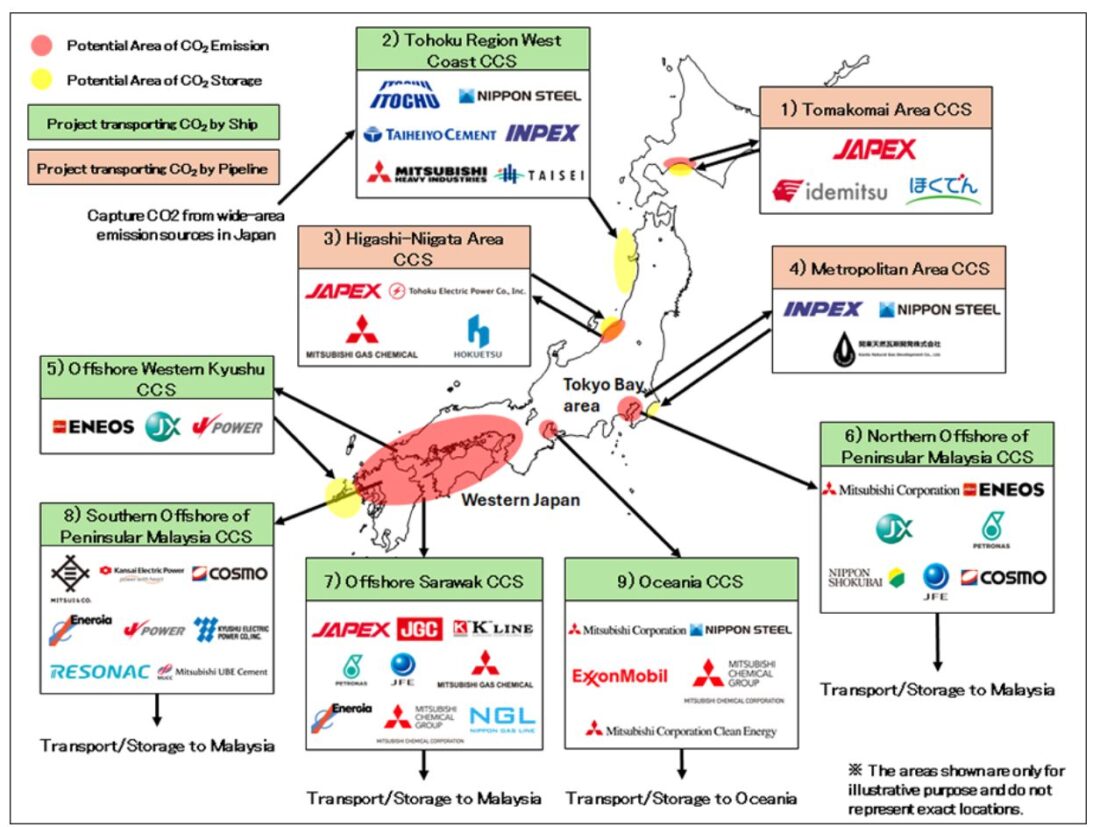

Location of 9 Japanese Advanced CCS Projects and companies

Prior to the enforcement of the CCS Business Act, the Japan organization for Metals and Energy Security (JOGMEC) publicly called for contract research work on “advanced CCS projects” and selected nine projects (five for domestic storage and four for overseas storage) as candidates in June 2024. In February 2025, the offshore Tomakomai area north of Hokkaido was chosen as the first location for exploratory drilling to develop commercial-scale CCS, and it is expected that exploration and exploratory drilling will proceed in the future.

CCS: Issues and challenges

Attaching CCS equipment to existing thermal power plants and continuing to use them is a major problem because it justifies continuous use of thermal power despite the availability of alternatives such as renewable energy. In addition, CCS also faces the following challenges:

1) Storage challenges

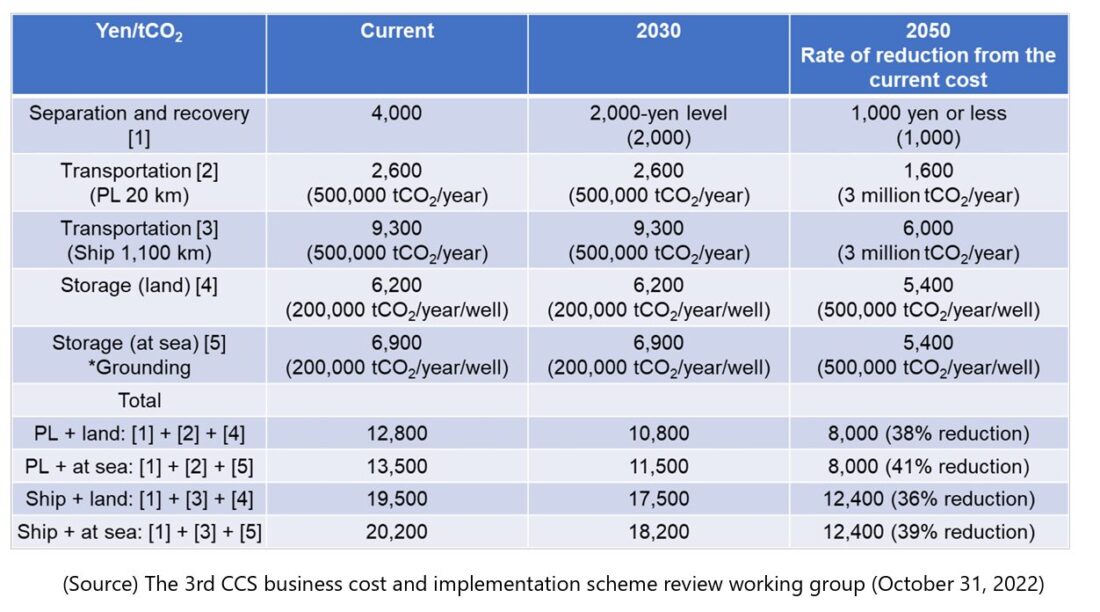

Most of the CCS projects currently in operation around the world are located near where the CO2 is generated, such as in former oil and gas reservoirs or coal mining sites, but the Japanese government is mainly considering liquefying the captured CO2, transporting it by vessels/ships, and injecting it into the seafloor. The Ministry of the Environment (MOE) has been conducting trial calculations and comparison studies of the potential and cost of laying pipelines to storage sites (sea floor), transporting CO2 by ship to the storage sites (sea surface) and injecting it from a ship to the well(s).

However, the capacity of storage sites is limited, and there are not many suitable sites for long-term CO2 storage in Japan. Due to limited domestic storage potential, many companies, including power companies, are participating in overseas CCS projects. However, there is opposition to cross-border CCS projects that impose emitted CO2 on other countries, with a letter submitted by NGOs calling such cross-border CCS projects “carbon colonialism”.

Moreover, shipping technology of liquefied CO2 has not been established at this point. Demonstration tests began in FY2021, aiming to establish that technology by 2026. Furthermore, negotiations with the countries receiving the CO2 are also necessary for cross-border CCS transport.

2) Cost challenges

The cost of CCS is one of its major challenges, with policy support being provided in many countries. METI has provided estimates of the expected cost reduction at each stage of a project, but it is clear that the cost of CCS is high: according to METI’s estimation, the cost of ship transport and offshore storage is 20,200 JPY/ton, and this cost is not expected to come down. If CCS is used in the power sector, its costs will be added to the price of electricity. Under the CCS Business Act, support measures to compensate for the high cost of CCS over the long term are being considered, and there is concern that this will increase the burden on the public.

3) Project development and operation challenges

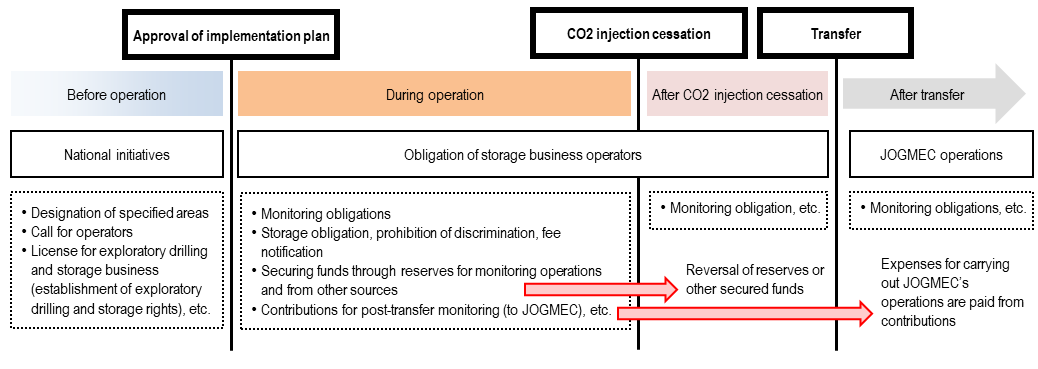

In March 2023, the “Long-Term CCS Roadmap” was introduced, aiming to start CCS projects by the end of 2030 and secure 6-12 million tons of CO2 storage annually by the same year. However, the CCS project flow does not include environmental assessment, so it is not clear whether an environmental impact assessment of the area around the injection wells will be conducted properly, and there is no way for local residents and citizen groups to voice their concerns.

Another problem is that the project flow for CCS is very complicated. The operator will conduct exploratory drilling and operation under a license granted by METI, but after CO2 injection, the management is transferred to JOGMEC, which is responsible for ensuring that there is no long-term leakage at the CO2 reservoir and for ensuring safety.

Therefore, the operator is not responsible for management after the injection is stopped. Nevertheless, the details and responsibilities of permanent management operations, including how JOGMEC will handle any problems or leaks that occur during monitoring, have not been clearly defined.

Current and future prospects of CCS projects

More and more CCS projects are under construction and in operation around the world. In November 2023, Australia passed legislation that will help facilitate carbon capture, utilisation and storage (CCUS), permitting companies to export CO2 from Australia for storage in offshore reservoirs in other countries. On the other hand, it has been pointed out that the actual CO2 capture rate in cases throughout the world has only been 60-70%, and analyses have been published showing that the capture rate in CCS projects at US power plants was as low as 55-58%. In any case, it is obvious that CCS is not an appropriate measure to be the cornerstone of a decarbonization strategy.

Based on the concept that CCS is essential to achieve the goal of the Paris Agreement, a business environment in Japan will be developed in accordance with the CCS Business Act and full-scale CCS projects will be promoted toward 2030. However, at a meeting of the government’s study group, there was concern that if CCS could not be introduced by 2030, it would be difficult to secure the annual CO2 storage required to achieve carbon neutrality by 2050.

Considering the small number of suitable storage sites, high cost, and the risk of leakage, sectors which have alternatives, such as the power sector, should be excluded from the scope of CCS projects. Nevertheless, at the Working Group for Policy Review established under the Electricity and Gas Basic Policy Committee Working Group (February 26, 2025), it was agreed that LNG- and coal-fired power plants with CCS will be included in the third round of the Long-term Decarbonization Power Source Auction. Thermal power plants with CCS will be required to have a minimum recovery rate of at least 20% at rated output, equivalent to the technically uncertain minimum mixing rate of 20% for ammonia co-firing.

Instead of attaching CCS to existing thermal power plants as a plan to decarbonize Japan’s power sources, there is an urgent need to reduce the number of thermal power plants and drastically reduce CO2 emissions.

Related Links

FoE Japan: Briefing Note: Japan’s CCS (Carbon Capture and Storage) Policy (Link)

Kiko Network: 【Position Paper】Carbon capture, utilization and storage (CCUS) is not a magic wand (Link)

Renewable Energy Institute: Bottlenecks and Risks of CCS Thermal Power Policy in Japan (Link)